Using healthy skin to identify cancer's origins

Normal skin contains an unexpectedly high number of cancer-associated mutations, according to a study published in Science. The findings illuminate the first steps cells take towards becoming a cancer and demonstrate the value of analysing normal tissue to learn more about the origins of the disease.

The study revealed that each cell in normal facial skin carries many thousands of mutations, mainly caused by exposure to sunlight. Around 25 per cent of skin cells in samples from people without cancer were found to carry at least one cancer-associated mutation.

Ultra-deep genetic sequencing was performed on 234 biopsies taken from four patients revealing 3,760 mutations, with more than 100 cancer-associated mutations per square centimetre of skin. Cells with these mutations formed clusters of cells, known as clones, that had grown to be around twice the size of normal clones, but none of them had become cancerous.

“With this technology, we can now peer into the first steps a cell takes to become cancerous. These first cancer-associated mutations give cells a boost compared to their normal neighbours. They have a burst of growth that increases the pool of cells waiting for the next mutation to push them even further.

“We can even see some cells in normal skin that have taken two or three such steps towards cancer. How many of these steps are needed to become fully cancerous? Maybe five, maybe 10, we don’t know yet.”

Dr Peter Campbell A corresponding author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

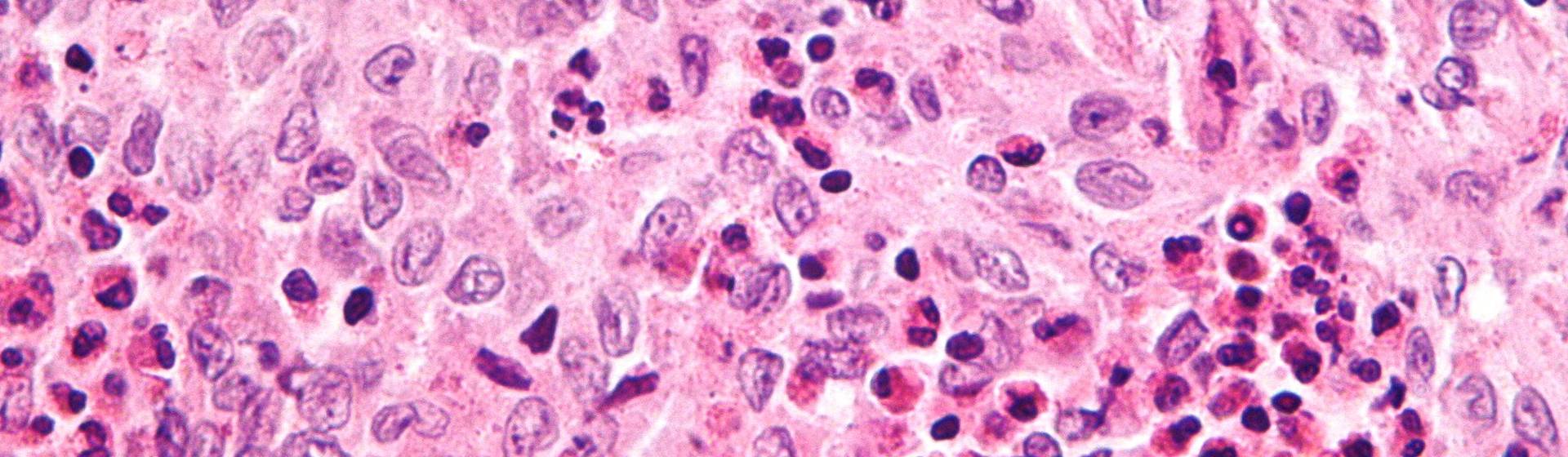

The mutations observed showed the patterns associated with the most common and treatable form of skin cancer linked to sun exposure, known as cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, rather than melanoma, a rarer and sometimes fatal form of skin cancer.

“The burden of mutations observed is high but almost certainly none of these clones would have developed into skin cancer. Because skin cancers are so common in the population, it makes sense that individuals would carry a large number of mutations. What we are seeing here are the hidden depths of the iceberg, not just the relatively small number that break through the surface waters to become cancer.”

Dr Iñigo Martincorena First author from the Sanger Institute

Skin samples used in this study were taken from four people aged between 55 and 73 who were undergoing routine surgery to remove excess eyelid skin that was obscuring vision. The mutations had accumulated over each individual’s lifetime as the eyelids were exposed to sunshine. The researchers estimate that each sun-exposed skin cell accumulated on average a new mutation in its genome for nearly every day of life.

“These kinds of mutations accumulate over time – whenever our skin is exposed to sunlight, we are at risk of adding to them. Throughout our lives we need to protect our skin by using sun-block lotions, staying away from midday sun and covering exposed skin wherever possible. These precautions are important at any stage of life but particularly in children, who are busy growing new skin, and older people, who have already built up an array of mutations.”

Dr Phil Jones A corresponding author from the Sanger Institute and the MRC Cancer Unit at the University of Cambridge

Recent studies analysing blood samples from people who do not have cancer had revealed a lower burden of mutations, with only a small percentage of individuals carrying a cancer-causing mutation in their blood cells. Owing to sun exposure, skin is much more heavily mutated, with thousands of cancer-associated mutations expected in any adult’s skin.

The results demonstrate the potential of using normal tissue to better understand the origins of cancer. The Cancer Genomics group at the Sanger Institute will continue this work with larger sample numbers and a broader range of tissues to understand how healthy cells transition into cancerous cells.

More information

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (077012/Z/05/Z); an MRC Centennial award; a Wellcome Trust senior Clinical Research Fellowship (WT088340MA); an MRC grant; a Cancer Research UK grant (programme grant C609/A17257); a fellowship from EMBO (1287-2012); a fellowship from Queens’ College, Cambridge and a CRUK-Cambridge Cancer Centre Clinical Research Fellowship.

Participating Centres

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute; Francis Crick Institute; MRC Cancer Unit, University of Cambridge; University of Leuven; Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge.

Publications:

Selected websites

Francis Crick Institute

The Francis Crick Institute is a unique partnership between six of the UK’s most successful scientific institutions. Its work is helping us to understand why disease develops and to find new ways to treat, diagnose and prevent illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

MRC Cancer Unit

The MRC Cancer Unit undertakes world-leading research into understanding how cancers develop, and seeks to translate this knowledge into new approaches for diagnosis and treatment that can be applied in the clinic, using innovative enabling technologies. Our focus is on discovering the earliest steps that lead to the transformation of normal cells into cancers arising in epithelial tissue, because we believe that better understanding of these steps will lead to new methods to improve the care and survival of patients with common and serious malignancies such as pancreatic, oesophageal, lung, breast and skin cancers.

KU Leuven

Situated in Belgium, in the heart of Western Europe, KU Leuven has been a centre of learning for nearly six centuries. Today, it is Belgium’s largest university and, founded in 1425, one of the oldest and most renowned universities in Europe. As a leading European research university and co-founder of the League of European Research Universities (LERU), KU Leuven offers a wide variety of international master’s programmes, all supported by high-quality, innovative, interdisciplinary research.

University of Cambridge

The mission of the University of Cambridge is to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. To date, 90 affiliates of the University have won the Nobel Prize. Founded in 1209, the University comprises 31 autonomous Colleges, which admit undergraduates and provide small-group tuition, and 150 departments, faculties and institutions. Cambridge is a global university. Its 19,000 student body includes 3,700 international students from 120 countries. Cambridge researchers collaborate with colleagues worldwide, and the University has established larger-scale partnerships in Asia, Africa and America. The University sits at the heart of one of the world’s largest technology clusters. The ‘Cambridge Phenomenon’ has created 1,500 hi-tech companies, 12 of them valued at over US$1 billion and two at over US$10 billion. Cambridge promotes the interface between academia and business, and has a global reputation for innovation.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.